|

|

Penelope. 1608: Roman copy of Greek work from 5th century BC. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

|

|

|

"Wife, one thing is certain—not all our soldiers will return from Troy unhurt … So I cannot say whether the gods will let me come back or whether I shall fall on Trojan soil. But I leave everything here in your charge. Look after my father and mother in the house as you do now … And when you see a beard on our boy's chin, marry whomsoever you fancy and leave your home." (Odysseus to Penelope, Homer, Odyssey 18.260).

"… In that catastrophe no one was dealt a heavier blow than I, who pass my days in mourning for the best of husbands …" (Penelope to the minstrel Phemius 2, Homer, Odyssey 1.340).

"Penelope must beware of trying our young men's patience much further and counting too much on the matchless gifts that she owes to Athena, her skill in fine handicraft, her excellent brain, and that genius she has for getting her way. In that respect, I grant, she has no equal, not even in story." (The Suitor Antinous 2 to Telemachus. Homer, Odyssey 2.115).

"Penelope is meaner to look upon than you in comeliness and in stature, for she is a mortal, while you are immortal and ageless. But even so I wish and long day by day to reach my home, and to see the day of my return." (Odysseus to Calypso 3. Homer, Odyssey 5.215).

|

|

Penelope waited two decades for her husband Odysseus to return to

Ithaca from the Trojan

War, not knowing whether he was dead or alive. In this long and painful wait her sole relief was to weep and sigh all day long, and to lie in what she called her "bed of sorrows" which she watered with tears until she fell asleep. In the meantime, she was compelled to promise the scoundrels that called themselves her SUITORS and who

were at the same time the pick of the Ithacan

nobility, that she would wed one of them when the

shroud of Laertes was finished. She wove it for

three years, weaving it by day and undoing it by

night. But her trick was discovered and her life

became even more difficult.

Her husband was one of the SUITORS OF HELEN

Odysseus was among

those who came to Sparta in order to compete for the hand of Helen, that jewel of Hellas who was afterwards called "Lady of Sorrows" because so many a man lost his life fighting for her sake in the plains of Troy . And yet, some say, this was the will of the gods. Helen's beauty was

such that her earthly father Tyndareus (for the

heavenly was Zeus) feared

that war would break up among the many princes who

had come from the whole of Hellas hoping to marry

her.

The Oath of Tyndareus

It was then that Odysseus told King Tyndareus to exact an

oath from all the SUITORS OF HELEN that they would defend the favored bridegroom

against any wrong that might be done against him in

respect of his marriage. Tyndareus did as Odysseus advised, and

having thus united the contenders by forcing them

to leave their honour as a pledge, he, in exchange

for Odysseus'

invaluable service, helped him to win the hand of Tyndareus' niece

Penelope.

Some consequences of the oath

This is what is called The Oath of Tyndareus. Thanks to

this oath peace was preserved among the SUITORS OF HELEN,

when Helen was given to Menelaus, and thanks to

it Odysseus married

Penelope. But later, on account of the same oath,

all princes of Hellas had to go to war against Troy, where Helen was kept, now

married to the seducer Paris, who had come to Sparta and abducted her.

And the same oath by which Odysseus won his wife,

forced him later to part from his prize for twenty

years, and live, against his will, the life of a

soldier and adventurer.

Does not wish to leave kingdom and queen

Now, Odysseus, who

was the king of beautiful isles and the husband of

a loving queen, not wishing to waste his life in

wars and fights, decided to feign madness instead

of honouring The Oath of Tyndareus, and thereby

join the alliance that was determined to sail

against Troy in order to

demand, either by persuasion or by force, the

restoration of Helen and

the property.

Palamedes destroys Odysseus' home life

And so, playing the fool, Odysseus put on a cap

and yoked a horse and an ox to the plow. But Palamedes, who had

come to Ithaca with Nestor and Menelaus in order to

remind the king of his oath, snatched little Telemachus from

Penelope's bosom, or as others say, from the

cradle, and put him in front of the plow, forcing Odysseus to give up his

pretense. Others have said that Palamedes threatened

the child with his own sword, but in any case Odysseus was outwitted

and had to join the alliance. However, clever Palamedes later paid

with his own death for having spoiled Odysseus' sweet home

life.

Odysseus won

Penelope in a foot-race

Others affirm that Odysseus won Penelope in a foot-race for her wooers, organized by Icarius 1. And they say that when he gave his daughter in marriage to Odysseus,

he tried to make him settle in Lacedaemon. However, Odysseus refused, and

he could not persuade Penelope either. So when the

newly-weds set forth to Ithaca, the king followed

the chariot begging her to stay. After some time,

they say, Odysseus, not

being able to endure any longer this expression of

fatherly love and devotion, bade Penelope either to

come with him willingly, or else go back with her

father to Lacedaemon, if she preferred to do so.

They say that Penelope did not reply, but instead

covered her face with a veil, and by that sign they

both understood that she wished to depart with her

husband.

Queen of Ithaca, Cephallenia and other islands

This is how Penelope came to Ithaca where she became queen of that island as well as others that are in the Ionian Sea off the coast of Acarnania, among which is the larger island Cephallenia, called after Cephalus 1, father by Procris 2 of Arcisius,

father of Laertes, father of Odysseus. Cephalus 1 was an Athenian, but he came to that region when he assisted Amphitryon in his campaign against the islands that were ruled

from Taphos.

The SUITORS OF

PENELOPE

Penelope and Odysseus had spent

together about a decade when the Trojan War broke up

and Odysseus left. The

war itself lasted ten years, but when it was over

and nothing was known of him, a group of scoundrels

known as the SUITORS

OF PENELOPE came to the palace wishing to marry

the queen.

The Shroud of Laertes (Penelope's web)

Penelope fooled them several years, declaring

that she would marry one of them once she had

completed the shroud of Laertes, for as she said:

"When he

succumbs to the dread hand of Death that stretches all men out at

last, I must not risk the scandal there would be

among my countrywomen here if one who had amassed

such wealth were put to rest without a

shroud." (Penelope to the SUITORS. Homer, Odyssey 2.100).

However, Penelope had no intention of ever

finishing her work, and so what she wove during the

day, she unravelled by night.

The SUITORS'

pleasant life

But when one of Penelope's maids gave her

mistress away, the SUITORS, having

caught the queen destroying her work, forced her to

complete it. And so, realising that they had been

fooled by her in the course of several years, the SUITORS decided

that for as long as she maintained her attitude,

they would continue to feast in the palace at the

palace's expenses. Otherwise they used to amuse

themselves in a free and easy way outside the

palace with quoits and javelin-throwing, a nice and

entertaining activity which they could consent to

interrupt when supper was ready. Their banquets

were prepared by slaughtering sheep, goats, hogs,

and heifers from Odysseus' herd. And

since banquets and music go together, there was

always someone playing the lyre. Such was the

pleasant life, free of charge, that the SUITORS led at Odysseus' palace.

Plot against Penelope's son

|

|

Penelope. 4910: Jens Adolph Jerichaü 1816-1883: Penelope 1843. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

|

|

This was the situation when Penelope's son Telemachus sailed to Pylos and Sparta in order to meet Nestor and Menelaus, with the hope

of having news of his father. But when the SUITORS learned

that the lad had determination enough to launch a

ship and choose the best men in the land for the

crew without saying a word to them, they, fearing

that Telemachus would

become their bane, planned to slay him on his

homeward way.

Herald overhears the SUITORS

When Penelope learned about the conspiracy through the herald Medon 5, who overheard the SUITORS, she

could not stop lamenting, seeing that the loss of

her child was about to be added to the loss of her

husband. And so she lay in her chamber, touching no

food, and pondering whether her son would escape

death, or be slain by the SUITORS.

Penelope's sister appears in her dreams

And nothing could soothe her but Sleep. For sometimes gods

talk to mortals during sleep, clear visions coming

in the darkness of Night,

and Sleep himself being a

god. So Athena fashioned a phantom of Penelope's sister Iphthime 1, and sent it to talk to her at the gates of dreams, and bid her cease from weeping and lamentation; for Telemachus, said the

phantom, was led by Athena herself. Penelope's sister Iphthime 1 married Eumelus 1, who led the Pheraeans against Troy and was the son of Admetus 1 and Alcestis,

the woman who died for love in her husband's place.

Harsh rebuke against the suitor Antinous 2

In fact Telemachus escaped the SUITORS' plot, and when Penelope learned what had happened, she harshly rebuked the main instigator Antinous 2:

"I denounce

you for the double-dealing ruffian that you are.

Madman! How dare you plot against Telemachus' life." (Penelope to Antinous 2. Homer, Odyssey 16.419).

Penelope then reproached Antinous 2, reminding him how his father had been once saved from an angry mob by Odysseus,

at whose expense he was now living free of charge,

whose wife he was courting, and whose son he

proposed to kill, disregarding the grief he may

cause to herself.

Condemns their style

And on a later occasion, she told the SUITORS that

even if the day approached when she would have to

remarry, she nevertheless condemned the way in

which they conducted their suit, saying:

"Surely it is

usual for the SUITORS to bring in their own cattle and

sheep to make a banquet for the lady's friends, and

also to give her valuable presents, but not to

enjoy free meals at someone else's expense." (Penelope to the SUITORS. Homer, Odyssey 18.275).

But the SUITORS, not

trusting her words after what had happened with the

shroud of Laertes, would not leave the palace nor

abstain from conducting the suit with such a

remarkable style.

Without defence

For, as Penelope herself pointed out, there was

no chieftain from the surrounding islands and from

Ithaca itself that was not forcing himself into her

house, plundering it. And that is why Penelope

could not feel but despair and neglect, passing her

days in sobs and tears for having lost her husband

and the protection of the household.

The Cat and the Mice

This invasion of Odysseus' home, which,

like a revolution, tended to seize all instruments

for the control of riches and power, came to an end

when the master of the house returned. For, as even

children know, the mice can only play while the cat

is away. On his arrival to Ithaca, Athena disguised Odysseus as a stranger

and a beggar, withering his limbs, robbing his head

of hair, and covering his body with the wrinkles of Old Age. He then came to Eumaeus 1, his former

servant and swineherd, and learned from him the

state of affairs in his home. And having met Telemachus in the hut

of Eumaeus 1, he made a

plan together with him.

Odysseus in the

palace

Still looking as a distressful beggar, limping

along with the aid of his staff, Odysseus came to the palace, where only his old dog recognized him, dying immediately after having seen his master in the twentieth year. There he came into conflict with Antinous 2, who was irritated at the beggar, and dealt him a blow.

Penelope talks to the stranger

But Penelope sent for the beggar; for such a

stranger who seemed to have traveled far, she

thought, might have heard of her husband. And not

recognizing Odysseus,

but being impressed by the stranger, she told him

the whole story of her misery, how she had fooled

the SUITORS with

the web, how they loaded her with reproaches on

discovering her trick, and how now she would be

forced by time and circumstances to take the sad

step of marrying one of the scoundrels.

The stranger's prophecy

When the turn came to Odysseus-the-beggar to

tell his own story to the lady of the house, he,

not wishing her to know his identity yet,

fabricated a tale about how he had met Odysseus, giving proof,

through many details, of his truthfulness. For he

could describe Odysseus' cloak and the

golden broch that it displayed along with other

details. But seeing that his descriptions made

Penelope even more disposed to weep, he said:

"… Dry your tears now and hear what I have to say … I have news of Odysseus' return, that he is alive and near …" (Odysseus to Penelope. Homer, Odyssey 19.269).

And after inventing other details which made the

story credible he finally declared:

"So you see that he is safe and will soon be back. Indeed he is very close … I swear first by Zeus, the best and greatest of the

gods, and then by the good Odysseus' hearth which I have come to, that

everything will happen as I foretell. This very

year Odysseus will be here, between the waning

of the old moon and the waxing of the new." (Odysseus to Penelope.

Homer, Odyssey 19.300).

Penelope enchanted

Even if Penelope, having deep despair in her

soul, could not believe in such prophecies, she was

enchanted by the stranger, and ordered the maids to

wash the visitor's feet, spread a bed for him, and

the next morning give him a bath and rub him with

oil, so that he would be ready to eat breakfast

with Telemachus in

the palace's hall.

|

|

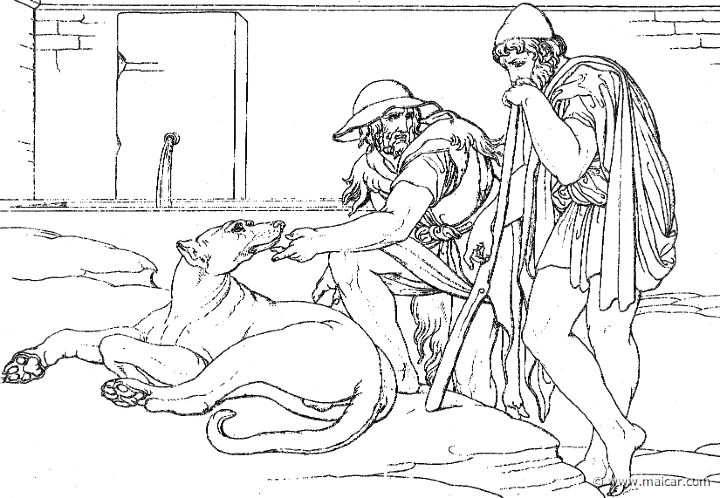

Eumaeus, Odysseus and the dog Argos | od339gen: "A hound that lay there raised his head and pricked up his ears, Argos, the hound of Odysseus, of the steadfast heart, whom of old he had himself bred." (Hom.Od.17.290). Bonaventura Genelli (1798 – 1868).

|

|

Euryclia recognizes Odysseus

It was then that Euryclia, the servant whom

Laertes had procured for the price of twenty oxen,

and who had been the nurse of both Odysseus and Telemachus, was

appointed to wash the visitor's feet. Now Odysseus had an old

scar just above the knee, and when the old woman

passed her hands over the scar, she recognized the

feel of it at once, and knew that this stranger was

indeed Odysseus.

However, he ordered her to keep silent.

Aspects of recognition

After Odysseus bathed his feet, Penelope addressed him once more,

still without recognizing him, which may seem an

amazing circumstance. For, despite the fact that Athena had changed his appearance, some may ask why it should be easier to identify a scar rather than a face, or the eyes in that face, or a familiar voice. But these things, being matter of opinion, may cause endless debate, as if one were to wonder why Penelope, being herself what is called "a myth," quotes freely from other "myths" in her conversation.

Tells her dream to the stranger

Penelope then, addressed Odysseus once more

after Euryclia had bathed his feet. And as if she

wished to make intimate acquaintance with him, she

asked him to interpret a dream of hers in which she

had seen herself keeping a flock of twenty geese.

And while she was with the geese, she saw an eagle

swoop down from the hills and break their necks.

Then, Penelope said, she wept and cried aloud. But

the eagle came back calling itself Penelope's

husband; and comparing the geese to the SUITORS, the

eagle told her to take heart, for they would be

punished at Odysseus'

soon homecoming.

What Penelope knows about dreams

And here again some could ask what need did

Penelope have of hearing the stranger's

interpretation of such an obvious dream, on which,

as Odysseus himself

points out, no other meaning could be forced

different from the one expressed by the eagle in

the dream itself. But Penelope knew better. For she

explained to Odysseus the true nature of dreams, and how there are two

gates through which dreams reach mortals; and one,

she said, is made of horn and the other of ivory.

And the dreams that come through the ivory gate

cheat us with empty promises, whereas those that

pass through the gate of horn tell the dreamer the

truth of what will happen. Yet she could not tell

from which source her dream took wing.

Penelope comments practical issues

Having shared with the stranger these ideas, showing to him her open disposition—for dreams are not usually told to those who do not seem to deserve confidence—Penelope commented practical issues. She said that her son Telemachus actually

desired her to remarry, for otherwise the SUITORS would

eat up his estate, and that she now was about to

propose a trial of strength, and that she was

prepared to marry whichever among the SUITORS proved

the best at stringing the bow and shooting an

arrow.

The SUITORS suddenly shot

So it was done. Penelope delivered to her SUITORS the bow

of Odysseus, saying

that she would marry him who bent the bow. And when

none of them could bend it, Odysseus took it and

shot down the SUITORS during a

great battle in the hall of the palace. This is how

the husband, who had been absent nineteen years,

won his wife for a second time while she slept in

her chamber upstairs.

Penelope wakes up to a new world

When the massacre was completed, Euryclia,

following Odysseus'

instructions, woke up Penelope with incredible

words:

"Wake up,

Penelope, dear child, and see a sight you have

longed for all these many days. Odysseus has come home … and he has killed the rogues who turned his whole house inside out, ate up his wealth, and oppressed his son." (Euryclia to Penelope. Homer, Odyssey 23.5).

Penelope, thus taken out of her sleep, thought

that her old servant had lost her brains, or that

some god had performed the killing. But Euryclia

told her about the scar, and nothing else could

Penelope do but go downstairs and see with her own

eyes what had happened by meeting her son Telemachus, the dead SUITORS, and the man who had killed them. Now she wondered: Should she remain aloof while talking to the

stranger, said to be her husband, or should she go

straight up to him and kiss him? Instead she came

and sat silent on the opposite side to Odysseus, not knowing

whether to rest her eyes on his face, or to look at

the stranger's ragged clothes.

Telemachus'

reproaches

This was not what Telemachus had

expected. For he had imagined that his mother would

sit at his father's side, asking questions and

talking. For after all, he reasoned, here was the

absent husband back, and there was so much to say

and to know. And that is why he reproached his

mother, telling her that her heart was harder than

flint. But Penelope replied:

"My child, the heart in my breast is lost in wonder … I cannot find a word to say to him; I cannot ask him anything at all; I cannot even look him in the face. But if it really is Odysseus home again, we two shall surely

recognize each other, and in an even better way;

for there are tokens between us which only we two

know and no one else has heard of." (Penelope to Telemachus. Homer, Odyssey 23.105).

Extraordinary bed

Such a token was their own bed, which Odysseus himself had

constructed, a detail only known by them. And now

he described how he had built it, bringing to

memory the olive tree, thick as a pillar, which

grew inside the court. For round this tree he built

the room, and lopping all the twigs off, he trimmed

the stem and used it as a basis for the bed itself.

Then he finished it off with an inlay of gold,

silver and ivory, and fixed a set of purple ox-hide

straps across the frame.

|

|

3627: Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, 1751-1829: Odysseus und Penelope, 1802. Landesmuseum Oldenburg, Das Schloß.

|

|

The common secret

When Odysseus had

described all these details for Penelope, he said:

"There is our

secret, and I have shown you that I know it." (Odysseus to

Penelope. Homer, Odyssey 23.202).

It was then that Penelope, seeing the complete

fidelity of the description, burst into tears, and

running up to Odysseus,

threw her arms round his neck and kissed him.

Recognition of love

This is how Penelope and Odysseus met and recognized each other after two decades of separation. Now there may be those that again will find it

strange that such a recognition does not occur

directly, but instead must pass through an

extraordinary bed. And having these people in mind,

some have said that the only true recognition

between Odysseus and

Penelope is the recognition of love. For it is

plain that neither beds, nor clothes, nor bows, nor

tokens of whatever kind would have any meaning

without love, no matter how true they might be:

"The queen

knew that the stranger was the king when she saw

herself reflected in his eyes, when she felt that

her love encountered Odysseus' love." (J. L. Borges, Un escolio).

Others have thought differently

But either because this story was found to pour sentimentality in excess, or because there have been those who never believed in Penelope's fidelity, or for other reasons, it has also been said that Penelope was seduced by Antinous 2, the greatest scoundrel among the SUITORS. However, there have also been those who have affirmed that Penelope was not seduced by Antinous 2, but instead by the more gentle suitor Amphinomus 2, who was known to enjoy Penelope's special approval for being an intelligent man and behaving correctly. In fact Odysseus himself

singled him out:

"Amphinomus, you seem to me to be a thoroughly decent fellow …" (Odysseus to Amphinomus 2. Homer, Odyssey 18.125).

With this gentle suitor, they say, Penelope had a love affair, and for that reason, they add, she was killed by her own husband. Yet others have said that Odysseus, having learned that Penelope had slept with the great scoundrel Antinous 2, sent her back to her father Icarius 1 in Lacedaemon. Later, they affirm, she came to Mantinea in Arcadia, and there she

bore Pan to Hermes, which is even

more incredible. And as things became more and more

entangled, some have asserted, fearing that things

would fall out of proportion, that this Pan is not Pan the god, but a man called after the god. Odysseus, some say,

died of old age as Tiresias had told him, but others have insisted in saying that he was accidentally killed by Telegonus 3, his own son by the witch Circe. They also

affirm that after Odysseus' death,

Penelope was made immortal by Circe and sent to the Islands of the Blest together with Telegonus 3.

|